Michigan’s Ghost Towns – Kensington Village

Did you know that beneath the bucolic waters of Kent Lake in the Kensington Metropark once existed a town bristling with life, death, and scandal? This is the story of the Village of Kensington, Michigan.

We begin in 1825, when great numbers of easterners, mostly from New York, began migrating to the Great Lakes region after the completion of the Erie Canal. By 1830, Michigan’s population was growing rapidly, which gave birth to many new settlements. While many of these early communities were successful and still exist today, others were destined to fail and have become ghost towns.

It was during this time that the Village of Kensington, Michigan (nicknamed “Kent”) had its origins. Kensington was part of the early developments in the southeastern Livingston County /southwestern Oakland County area that also included the towns of South Lyon, Milford, and New Hudson. These were predominantly farming communities created by clearing the heavily forested terrain. Kensington’s location on the Grand River Indian Trail at the terminal of canoe navigation on the Huron River made it a favorite native American camping ground, which was frequented by early traders hoping to bargain with the natives that populated the valley. According to Kensington pioneer L.D. Lovewell: “The lake and bluffs on the north and the Huron River running through the center of the village made it one of the most desirable locations for a village I have seen in this part of the state.”

Borrowing from the old English name, Kensington was settled in 1831 with its town center in the northwest corner of Lyon Township. In 1833, on the bank of the Huron River, Joel Redway constructed the town’s first buildings: a log house and a sawmill that he operated. Town officials believed that the vast amounts of lumber and water power from the river would allow Kensington to grow into a major city center like Detroit. In the words of Kensington pioneer Sylvester Calkins: “A large flour mill was to be built the very next venture, and expectation stood on top-toe ready for anything wonderful to happen at the highly favored location. Under this feverish excitement the place was planned for a village on a large scale: with some room left, however, for addition on several sides. Lots were sold to actual settlers, who proceeded to erect their buildings, small and unpretentious in the majority of cases with a few very respectable ones, giving an air of aristocracy to the wondering gaze of the backwoodsman of those early days; also giving what was considered a sure prophecy of coming greatness and renown.”

On September 5, 1834, the Kensington Post Office opened at present day Kent Lake Road between Grand River Avenue (U.S. Route 16) and Silver Lake Road. The post office was located in the home of Abe Wood, as it was common in those days for buildings to serve a dual purpose. (Mr. Wood went on to serve in the Civil War, during which he lost an arm.)

In 1836, the Village of Kensington was platted over a square mile area and lots were selling at high prices. “Under this inspiration many bought lots on speculation at from forty to one hundred dollars per lot,” wrote Sylvester Calkins, “considering themselves fortunate in being able to secure such a fine investment for their little hard-earned capital.”

The village of Kensington, Michigan as it appeared in 1836. Handwritten notations on the map read: “State of Michigan, County of Oakland. Personally came before me on the twenty third day of November A.D. 1836 the undersigned Justice Alfred A. Dwight, the proprietor of the within plate (sic) of the village of Kensington and acknowledged it to be a true copy of said village according to the survey of A.E. Nathan, civ. eng. Parley W.C. Gates, Justice of the Peace. Received for recording 26 Nov. 1836 at 7:00 p.m. Vol. 13, page 129.” Also what appears to be a more current notation: “Part of John Dally’s farm.” Image courtesy of the Green Oak Township Historical Society.

Among the individuals who came from the east and contributed to Kensington’s early success were merchants Charles Cogswell and brothers Chauncey L. Crouse and Robert D. Crouse. Neil F. Butterfield opened a boot and shoe shop and purchased a large parcel of land on the south side of Grand River, precisely where a Mobil gas station and the Kensington Park Apartments exist today. John Dally, a well-heeled gentleman from New York, opened a brick store on the east side of town and served as postmaster for many years. George W. Peck and his brothers opened a store on the west side of the river. Caleb Carr erected two hotels and Alfred A. Dwight hired the Smith brothers, local carpenters, to build a frame general store, which Mr. Dwight stocked heavily with merchandise.

Additionally, the town boasted a tavern called the Kensington Inn, which also served as the offices for the two town doctors, Dr. Thomas Curtis and Dr. Wells. It is said that the good doctors were not licensed medical practitioners and that, with the prevalence of ague, typhoid and other afflictions, they built a very busy practice dispensing proprietary medicines such as quinine and calomel. Dr. Curtis also served as the town dentist, using whiskey from the tavern as the anesthesia of choice.

Other notable residents included Justice of the Peace Parley W.C. Gates, a native of Candandaigua, Ontario County, New York; and an attorney named Kinsley Scott Bingham. Mr. Bingham established a handsome homestead south of the village that still stands today. He went on to become a U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator as well as the 11th Governor of Michigan in 1854, serving two terms. Mr. Bingham was the first Republican Governor of Michigan and is one of the first Republicans to be elected governor of any state.

Before long, the village was prospering with three hotels catering to guests as well as a large livery stable, three general stores, two large shoe shops, five blacksmith shops, a flour mill, two brick yards north of town, and the first Baptist church in this area of the state. Presbyterian and Protestant Episcopal congregations soon followed.

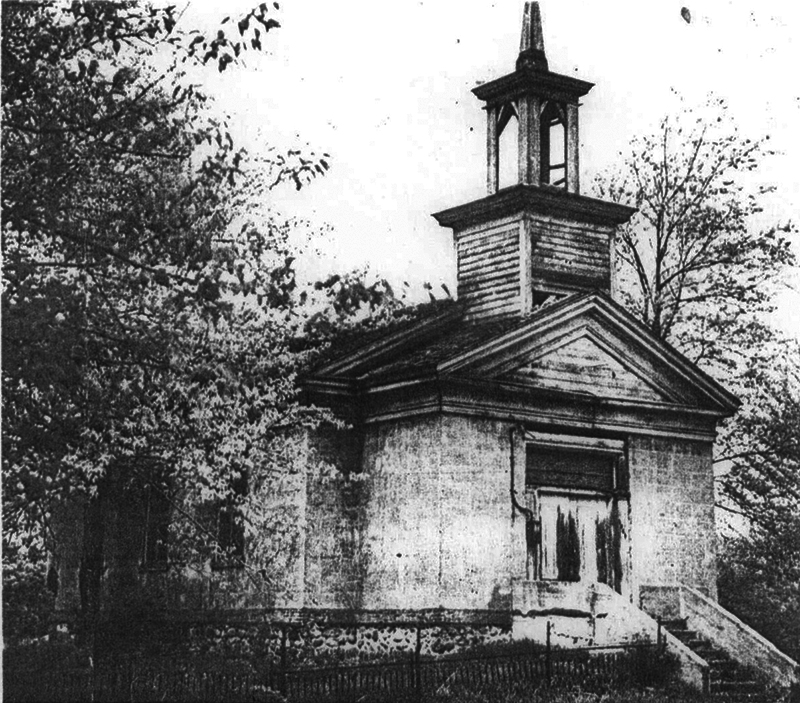

The Baptist Church in Kensington, Michigan, founded in 1839 and dedicated on October 11, 1853. It was located on the northwest corner of present-day Grand River Avenue and Kensington Road and stood until 1952. Photo by John Kingsley of Milford, Michigan from the Detroit News Pictorial Magazine (March 22, 1953). Image courtesy of the Green Oak Township Historical Society.

Ladies of the Kensington Baptist Church Society. Left to right (front): Mrs. Charles Foote, Mrs. Charles Cogswell, Miss Post, Mrs. J. Stevenson. Left to right (back): Mrs. James Collett, Mrs. Frank Michols, Mrs. Kinsley Scott Bingham, Mrs. Ella Beach, and Mrs. Clark Coe. Image courtesy of the Green Oak Township Historical Society.

In its earliest days, town officials proposed that the Huron River be dammed upstream in order to provide ample water power for the new town. “Who can tell what the next fifty years may give to this place?” Sylvester Calkins asked his fellow townsfolk. “The abundant waters of the Huron that now ceaselessly flow unimproved through this place may yet be utilized. The inventions of the age may yet redeem this place to its inhabitants, may yet consecrate it to industry, and industry may bring to it an abundance of wealth.” But the landowners in that area feared that the dam would flood their properties, so they blocked the plan.

Yet Kensington continued to grow and flourish. The town’s popularity rose quickly as a stagecoach stop for travelers on the Grand River Trail, which was becoming a booming government toll road from Detroit to Grand Rapids heavily traveled by ox teams. As L.D. Lovewell remembered: “This was before any railroads were built in Michigan, and the string of teams that were bringing in the people that were coming in from the eastern states to settle in Livingston, Ingham and the other western counties were immense. Also the wonderful amount of farm produce that went down the pike, the same wagons bringing back great loads of supplies for the farm, store and shops was something to remember. I can well remember when (I was) a boy seeing over 100 teams in a string. What seemed to me a great stage line, two four-horse coaches each way every day, besides the extras that often had to be used were in operation.”

It was said that Kensington had grown larger than New Hudson and was doing as much business as Milford. Word spread and, soon, many more wealthy men from the east began investing in Kensington real estate. As a result, on December 12, 1837, the Kensington Bank Company was founded by a group of village investors that included Alfred A. Dwight and Sherman D. Dix. Serving as both director of the bank and as cashier, Mr. Dix established a large farm just east of Woodruff’s Mills (later the Village of Livingston) and was said to have been “a man of much polish of manner, adroit in business, with a keen eye for a bargain, and one of the most generous and kindly neighbors that an early settler could desire.”

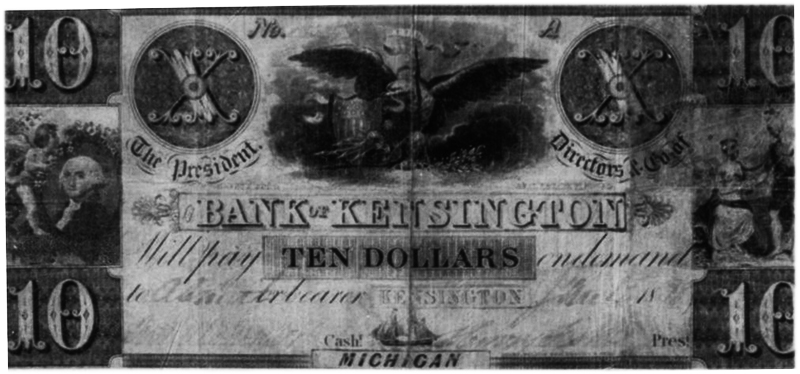

One must keep in mind that, at this time, Michigan was part of the American frontier and, as such, was a mostly unsettled wilderness that was rife with lawlessness and speculation. In these remote areas, the Freeholders’ Law had given birth to “wildcat” banks, which were intended to relieve the state legislatures of the burden of having to pass special chartering ordinances to allow banks to open. The Kensington Bank Company was one of those “wildcat” banks. By a manipulation of stock, the bank’s founders managed to entice several local men of means into the scheme. The bank’s Board of Directors included Alfred A. Dwight, Sherman D. Dix, B.P. Hutchinson, Chauncey L. Crouse, Neil F. Butterfield, A.M. Brown and C. F. Cooke. Stockholders included Joel Redway, Joseph Wood, and Kinsley Scott Bingham. The Bank of Kensington opened for business on a typical “wildcat” bank shoestring — a borrowed $50,000 certificate of deposit was its sole capital. In 1838, after receiving certification by the Farmers and Merchants Bank of Detroit, the Kensington Bank officials began issuing currency which was touted to be “as good as gold”.

“They obtained a good supply of bank note blanks that were soon properly signed and put in circulation. Let it be recorded that the Bank of Kensington issued as nice bills to look upon as any bank ever issued,” wrote Sylvester Calkins.

Although the excitement of the town’s rapid growth ran high, no single event generated more enthusiasm and anticipation than the establishment of the Bank of Kensington. “With such flattering prospects and such possibilities before these pioneers,” Sylvester Calkins stated, “it ought not perhaps be thought strange that these enterprising men should desire a bank from which they could issue bank-bill, deposit their surplus money, obtain drafts, and transact the immense commercial business of the place.”

The town’s future looked very bright. At its high point, Kensington’s population peaked at over 300 residents living in as many as 50 homes scattered about the area. With so many investing in a town brimming with such high hope, why is it that Kensington is no more?

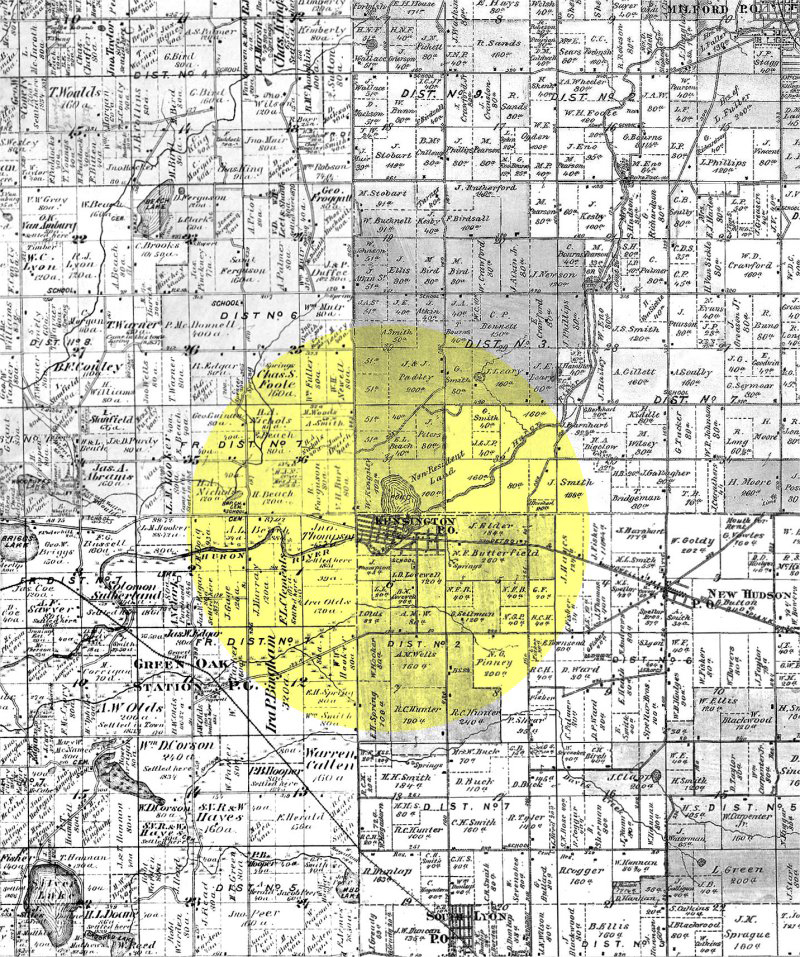

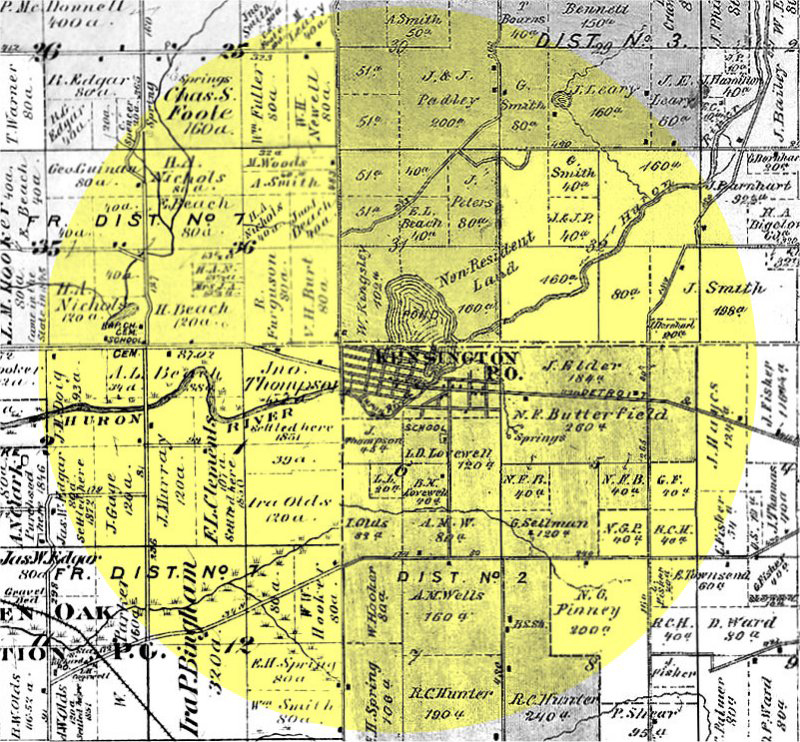

Kensington, Michigan can be seen in the highlighted area of this 1870s plat map composite. Plat map images courtesy of The Memorial Library and McCormick Books.

Kensington, Michigan can be seen in the highlighted area of this 1870s plat map composite. Plat map images courtesy of The Memorial Library and McCormick Books.

It was not a single isolated incident which brought about the demise of Kensington but, rather, a domino-effect of unfortunate circumstances. In fact, one could say that Kensington’s sad fate was sealed even as the town was being built. Had the Huron River dam project not been blocked by local farmers, Kensington may have been able to take advantage of the Industrial Revolution taking place all around it. But sadly, the overall lack of adequate water power for the town’s enterprises became the first nail in Kensington’s coffin.

Then hard misfortune struck Kensington. In 1839, a national banking crisis that had begun two years previous finally hit Michigan. As a result of the recession that followed, Kensington Bank’s note sales did not proceed as well as was expected and established banks “where a wildcat wouldn’t go” made it nearly impossible to redeem the notes, further slowing the circulation of the currency. To make matters worse, as a typical “wildcat” bank, the Bank of Kensington printed more money that it had specie in vault. That fall, after the crops were sold and the bank was flush with cash, Dwight and Dix emptied the bank’s coffers and escaped to Milwaukee. There, it is said that they disposed of $50,000 in newly issued notes on jewelry, land, and livestock and pocketed the remaining money. According one source, however, some historians believe that Dwight and Dix were honorable in their intentions; that their transactions in Milwaukee were an act of desperation to save the bank by securing new assets.

At that time, the State of Michigan passed laws requiring banks to show real estate security but, after the disappearance of Dwight and Dix, the remaining holders except Crouse and Butterfield recorded their land titles to their wives’ names. As the only two landholders still holding real estate security in the bank, Crouse and Butterfield issued a reward for the return of Dwight and Dix. Shortly afterwards, Dwight and Dix were arrested in Wisconsin and returned to Michigan. There is no record of the results of the court proceedings or what became of the men, though one source indicates that Dix moved to Texas and engaged in cattle speculations. Although most of the money was later recovered, the Bank of Kensington soon closed due to a lack of assets. Kinsley Scott Bingham, who was at that time speaker of the State House of Representatives, was appointed as the receiver.

As Kensington’s economy began to fail in the wake of the bank scheme and the enforcement of the Wholesalers’ Act, village merchants stopped paying their bills and many residents left town without notifying their creditors. Eventually, the eastern investors boycotted the village and came to Kensington to collect on the debts, only to find mostly vacant homes and stores. This gave rise to a then-popular proverb wherein uncollectable debts became known as money that had “gone to Kent.” Suddenly, the little town of Kensington, Michigan was nationally notorious.

After the collapse of the Kensington Bank Company, the bank notes it had issued became worthless. Today, the very rare Bank of Kensington notes are highly prized among collectors and often demand prices far above their face value. The signatures of Fred Hutchinson, Cashier, and Henry Fisk, President can be seen on the surviving notes.

A surviving $10 Kensington Bank note. These very rare bank notes are highly prized among collectors. Image courtesy of the Green Oak Township Historical Society.

The Kensington Bank scandal devastated the Village of Kensington. Even before the Civil War began in 1861, many of Kensington’s structures had either disappeared or were being repurposed. The empty Kensington Bank Company building, on which construction had only just been completed when the bank failed, was used for many years by A. Wooton as a granary.

The remains of the Kensington Bank Company building on the north side of Grand River at the eastern boundary of Livingston County. The building was constructed of red brick with white pillars and a portico. It was occupied until 1920 when it fell into disrepair and by September of 1931, its remaining walls were demolished. Image courtesy of the Green Oak Township Historical Society.

The final blow to Kensington came in 1871, when rail lines were built in the area. Because railroads were considered to be the future of mass transportation, being included on a rail line was critical. The local towns competed with each other to attract the rail companies. In the end, Milford and South Lyon were on the Detroit, Lansing and Lake Michigan Railroad routes, but Kensington was passed by.

As a result, the town suffered another significant population loss that was further exacerbated in 1882 when the Michigan Air Line Railroad went through New Hudson. When it was clear that the new railroads had all left Kensington behind, the village began its final decline.

“Presto change, the bank failed, the dam went out, men failed in business,” wrote L.D. Lovewell. “The building of the D.L. & N. railroad stopped the travel on the pike so that the history of Kensington exists as a tradition. Many men left their homes and a good share of the town was sold for taxes; many good homes were abandoned. The material made good kindling wood for filling the jacks we used in spearing fish (we did not have gasoline then).”

Sylvester Calkins also remembered Kensington’s early destruction. “The mill went into decay and tumbled down, the best buildings were actually left without inhabitants and their ruin was not left for the comparatively slow process of time to accomplish, the shedding was torn off and the floors torn up to make kindling wood for those who remained. The large hotel built by Mr. Carr on the west side of the river was one of the buildings that disappeared in this manner — a little at a time until not a vestige remained to mark the spot.”

On July 31, 1902, the Kensington Post Office in Abe Wood’s home was closed. By 1905, there were only four families left in the village. In 1920, the Kensington Bank building, which was then occupied by the Free Wesleyan Methodist Church, was relegated to use as the local postmaster’s storage shed when Grand River was widened and paved. By the 1930s, most physical evidence of town’s existence had vanished. Only a handful of Kensington’s buildings still stood and the surrounding farms were disappearing quickly. The old Bank of Kensington building was finally completely demolished in 1931.

In 1940, the State of Michigan instituted a new plan to dam the Huron River upstream from Kensington, this time not for industry but for recreation. Over one hundred years since the first dam proposal, there were few remaining local residents to raise opposition and the new Huron-Clinton Metropolitan Authority dam project went through. As a result, the entire portion of the Village of Kensington in the valley of southwestern Milford Township was flooded, thus creating Kent Lake and the Kensington Metropark, which opened to the public in 1948. In the 1950s, construction of the I-96 highway began and whatever remained of the Village of Kensington south of Kent Lake was leveled. The one exception was a house that was moved to Brighton. When the Kensington Baptist Church was razed in 1952, the last standing reminder of the Village of Kensington was gone.

Today, the only remaining ruins of the Village of Kensington can be seen by visiting the Nature Center located at the western edge of Kensington Metropark. Along the Aspen nature trail, you can find the remnants of at least two houses along with various farm equipment, fences, and more scattered throughout the nearly one and one-half mile wooded area. To reach the nature center, exit I-96 at Kensington Road (exit 151). The park entrance is just north of I-96 on the east side of Kensington Road. Proceed down the park road about two miles to the entrance of the nature center on your left (north) side. There is a $7 per day admission fee to the park (as of today’s date).

Along the nature trails of Kensington Metropark lies a stone chimney, ruins of a house that was once a part of the Village of Kensington.

Near the Nature Center of Kensington Metropark is the stone foundation of another house that was once a part of the Village of Kensington. The marker here reads: “Bubbling Waters. Joe Labadie, a prominent Detroit journalist, poet, and labor leader, summered here with his family from 1912 until his death in 1933. Today, you can view the stone foundations and a living legacy of domesticated flowers – lily of the valley, iris, and periwinkle – which perpetuate themselves year after year.”

Rusting farm equipment left behind when the Village of Kensington became a ghost town. The Kensington Metropark marker here reads: “The sound of a dinner bell rings across the field. The team is unhitched and the long trek to the farmhouse for the evening meal begins. The farmer’s day is nearly over. Today, not much of this field or that way of life remains. Slowly, this field is becoming a forest while man’s machinery rusts away.”

Also in the area of I-96 and Kensington Metropark, there are two cemeteries formerly belonging to the Village of Kensington.

Kensington Cemetery No. 1 is located on the western edge of Kensington Metropark where the southwest park entrance meets Grand River, Kensington Road, and I-96, which straddles Oakland and Livingston counties and also Milford, Green Oak, and Lyon townships. Here, a brass marker attached to a large boulder designates the location of the Kensington Baptist Church pictured above. The cemetery was still active for burials as of 2010. Not far west of here was the old Village of Livingston, which included a toll gate for the Grand River plank road near Pleasant Valley Road.

Brass marker at the entrance to Kensington Cemetery No. 1. The marker reads: “Kensington Baptist Church, founded 1839, razed 1952”. The church was replaced with this marker after Kensington Cemetery board members gave the church building to the Reverend C.G. Morris, who salvaged its materials to be used on the construction of a new church in Novi.

What appears to be a 19th century-era water pump on the grounds of Kensington Cemetery No. 1. A relic from Kensington Village?

Kensington Cemetery No. 2, first named Kent Cemetery, is located on the south side of Grand River Avenue along I-96 just west of Kent Lake Road at the Oakland / Livingston county line. The town center of Kensington was located just east of this cemetery. It is relatively modest in size with only about 30 graves still identifiable. It seems as though, judging by the amount of empty spaces between the graves, that some of the graves have been moved. The most recent burial appears to have taken place in 1925.

The cemetery is in Oakland County but is maintained by the Green Oak Township Historical Society of Livingston County. To reach the cemetery, follow Grand River west toward Brighton. Just before you reach the Kensington Metropark Shooting Range, you’ll see the cemetery on your left about 15 feet off the road. There are two or three parking spaces alongside the road and access into the cemetery is made through a narrow opening in a metal fence at the east end of the property.

The State of Michigan still recognizes Kensington as an unincorporated community at Grand River Avenue on Kent Lake. Kensington no longer exists as a town but the name survives as the first of the Huron-Clinton Metroparks that were established in the five-county region around Detroit. Below you will find a map indicating the various locations discussed in this article.

In the words of L.D. Lovewell:

As the years continue to pass, fewer and fewer people can still recall this mostly forgotten place. I grew up in nearby South Lyon, Michigan but had never been told the story of Kensington and, although I’ve lived in the area most all my life, I never knew of the existence of a town called Kensington, Michigan until this past year.

Among the ruins of Kensington Village along the nature trails at Kensington Metropark, a marker reads:

By telling this story, we keep alive the memory of the Kensington pioneers who paved the way for us to pursue our hopes and dreams — much in the same way that they did so long ago.

Note: If anyone has photographs or other visual materials related to Kensington, Michigan that may be included in this article, please email me at kristina@kristinascarcelli.com or send me a message using the comment form below. Full credit will be provided. Thank you!

Works Cited:

The Detroit News Pictorial Magazine. Detroit: March 22, 1953.

Hamilton, Lyle. Livingston County Birding Areas and List. 2004.

Hataling, Bob. “The Ghost Town of Kensington”.The Milford Historian, September / October 2004.

History of Livingston Co., Michigan With Illustrations and Biological Sketches, It’s Prominent Men and Pioneers. Philadelphia: Everts and Abbott, 1880: p. 222.

“Kensington: Tombstone For a Dream”. The South Lyon Herald, August 27-28, 1969.

Louie, Barbara G. Northville, Michigan: The Making of America Series. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2001: p. 25.

Lovewell, L.D. “When Kent Was a ‘Live Town’: Some of the History of Kensington Village As Told by the Late L.D. Lovewell, South Lyon Pioneer”. The Milford Times, January 10, 1930.

Lyon Township Master Plan. April 9, 2012.

Michigan: A Guide to the Wolverine State. Michigan State Works Progress Administrative Board: Michigan Writers’ Project, 1941: p. 417.

Nusbaum, Chuck. “The Grand River Trail”. The South Lyon Herald, October 2, 1985.

Schweikart, Larry. A Patriot’s History of the United States: From Columbus’s Great Discovery to the War on Terror. Penguin, December 29, 2004.

Yesteryears of Green Oak, 1830-1930 1st Edition. Green Oak Township Historical Society, 1981: pp. 152, 158-162.

Online Sources:

Brighton Area Historical Society: Banking in Brighton by Marieanna Bair (March 27, 2009)

Exploration Guides: Kensington Metropark

Genealogy Trails: Lyon Township, Oakland County

RootsWeb GATES Archives: Report from Marion Brown

RootsWeb Oakland, Michigan Archives: Report from Mike Placco, Macomb College

StrangeUSA: Kensington Village

USGenWeb Archives: Kensington Cemetery No. 2, Livingston / Oakland County

Previous Post

Previous Post

Enter your email address below to subscribe.

Enter your email address below to subscribe.

I am a great granddaughter of N.F. Butterfield. I barely knew the history of Kensington,thank you for this information.

I recently learned of Kensington and appreciate your research and writing here on the topic. Thank you very much!

I have lived in Green Oak Township for 15 years and never heard of the town of Kensington. Thank you for opening my eyes.

You’re welcome, Tom! I had no idea it ever existed, either.

Thank you for this article!

Some of my ancestors were among the original settlers in Green Oak Townswhip. John Duncan Taylor, brother of my great-great-great-grandfather, married Betsey Gates, daughter of Parley Warren Gates who is mentioned in this story.

In my youth I hiked and camped at Kensington and Island Lake parks. I had no idea then of the history of the town nor of my relatives who lived and died in the area.

This is an amazing article. I have known about Kent for a long time now, but love the newer point of view. Thank you for the infomation.

Thank you Jennifer! It was fascinating to research. Hope you are well!

I am very VERY impressed by the thoroughness of this article –

Top notch!

Thanks so much! Coming from you, that is a tremendous compliment!

Such a great article! I have been looking for history in the area to teach my children about. Thank you for sparking interests for them.

Great article! I completed some research around 1985 focusing on “Kent”, after building a metal locator. I was intrigued by this piece of history. I actually found some of the old foundations on top of the hill just south of 96 and east of Kent lake, which is also south of 96 and just west of the “hill”.

Thank you so much for the article, very interesting research.

Thank you, Laura! Glad you enjoyed it.

Wonderful article! I really enjoyed reading it. I can’t wait to get out to Kensington to start investigating the ruins. Thank you,

Diane Cassar

Thank you Dianne. I’m glad you enjoyed the article. Be sure to feed the wild birds when you get there — they are amazing!

Very good article, since I’ve lived in the area for 50 years. Had no idea of the history of Kensington.

First off, I would like to thank you for writing the article on the Village of Kensington. I have lived just outside of the park my “whole” 22 years of living. I initially read this article back in 2015 when I was working for the DNR at Island Lake State Park. Trust me, I told everyone about it and no one could believe that there used to be a city in that area.

I have always been a history buff and do a fair amount of metal detecting around the areas, where I legally can. I have found old hammer forged nails just south of 96 and east of the cemetery off of Grand River closer to Kent Lake Road and plan to do some more this upcoming fall. I just recently was able to obtain a $20 bank note from the Kensington Bank that is from 1838 and it is extremely cool to have that piece of history.

Your article inspired me to look into the history of Island Lake State Park, and it was neat to check out some surviving foundations within the area that are mostly overlooked. While working there we used “the Gage Barn” to store extra equipment and I always thought it was cool because I knew the history of that same exact barn which was built around 1875. Supposedly, there are also unmarked graves from the Gage family on that property but that was my manager’s speculation.

I have visited Colonel Sutherland’s house foundation just west of the Riverbend picnic area, and have done some hiking through the woods south of the railroad near the “Dodge” parking lot. I think one of the coolest things I found so far was a 3-ringed bullet from the Civil War. Not quite sure what it was doing up here in Michigan. The only thing I can think of was that the 33rd and 34th regiments of the Spanish American war could’ve left it (they had a camp in the park) but I’m not sure if they used the same musket bullets at that time. The bullet is pretty well preserved, it was shot and is caved in a bit, which makes me wonder what it hit (hopefully not a person) and I found it about 12 inches underground, south of the old Sutherland Road which you can still see the outline of in the fall when the leaves are down.

Thank you for writing the article on the Village of Kensington, it has made me appreciate this area that much more and I hope other people will read it and feel the same. If you ever want to write an article on Island Lake and the history there I would be glad to contribute!

This is the most comprehensive article on Kensington Village. Years ago, I had talked to a parks employee who knew a lot about Kensington Village. He had some interaction with Mr. LaBadie. I wish I was interested in Michigan History back then.

I grew up at Island Lake. I enjoyed hearing the history of Kensington. My parents married in 1922, traveled from Detroit to Lansing visiting family in the 1920’s, they always made stops in Brighton. Eventually moving from Detroit to Island Lake in the ’50’s, I wish they could have read this history. I enjoyed taking my kids to Kensington and now take my grandchildren there. Thank you for history of Kensington.

I live in Green Oak Township. If you haven’t yet gone to the township office, they have an amazing collection of old photos and plat maps of the the township and surrounding townships. Not sure if they have any of the old Kensington township but it’s a resource if you haven’t yet been.

There was a stonewall on the north side of Grand River East of Kent Lake Road that was a piece of some old building. The Huron Valley Trail now runs next to it.

My ancestor’s a buried in Kensington Cemetery #1. I have never heard of this story until now. Thank you for all the hard work you have done.

Is there a listing of people buried in the Kensington cemetery, 1 & 2?

My 3rd great grand mother died in Kensington on December 26, 1845. I have not been able to find where she was buried. Can you help?

Thank you so much for writing this. My family and I have visited Kensington Metropark countless times and it’s so nice to find out more about its history,

Thank you for this history of Kensington Village. You have done the research that provides an inside look at this early community.

Years ago I saw a television program that explained that many early western movies were made in Kensington to prior to the industry moved to California and was headquartered in New York.

I was amazed at the research, history, photos that you provided, in fact I was extremely impressed. I live just outside of the boundaries of that village. I was surprised that I had not heard of you given your accomplishments after all after all l have lived in This general area for 74 years. My curiosity had me do a little research on my own. You photos are awesome and your voice is awesome as well. My wife and I really liked “I want to be your fantasy”

Your varied interests and talents make you a very special person and I will be following you hereafter.

Thanks again for your fantastic article.

Joe Borghi

I noticed Kensington Cemetery while driving by and finally stopped to visit. The gravestones are so weatherworn that some are hard to read. One read born 1799, which completely floored me. I had to know and so looked up who was President then and found it was John Adams. This woman missed being born in George Washington’s presidency by two years! Further intrigued, I discovered Kristina’s article which I thoroughly enjoyed. Thank you, Kristina.